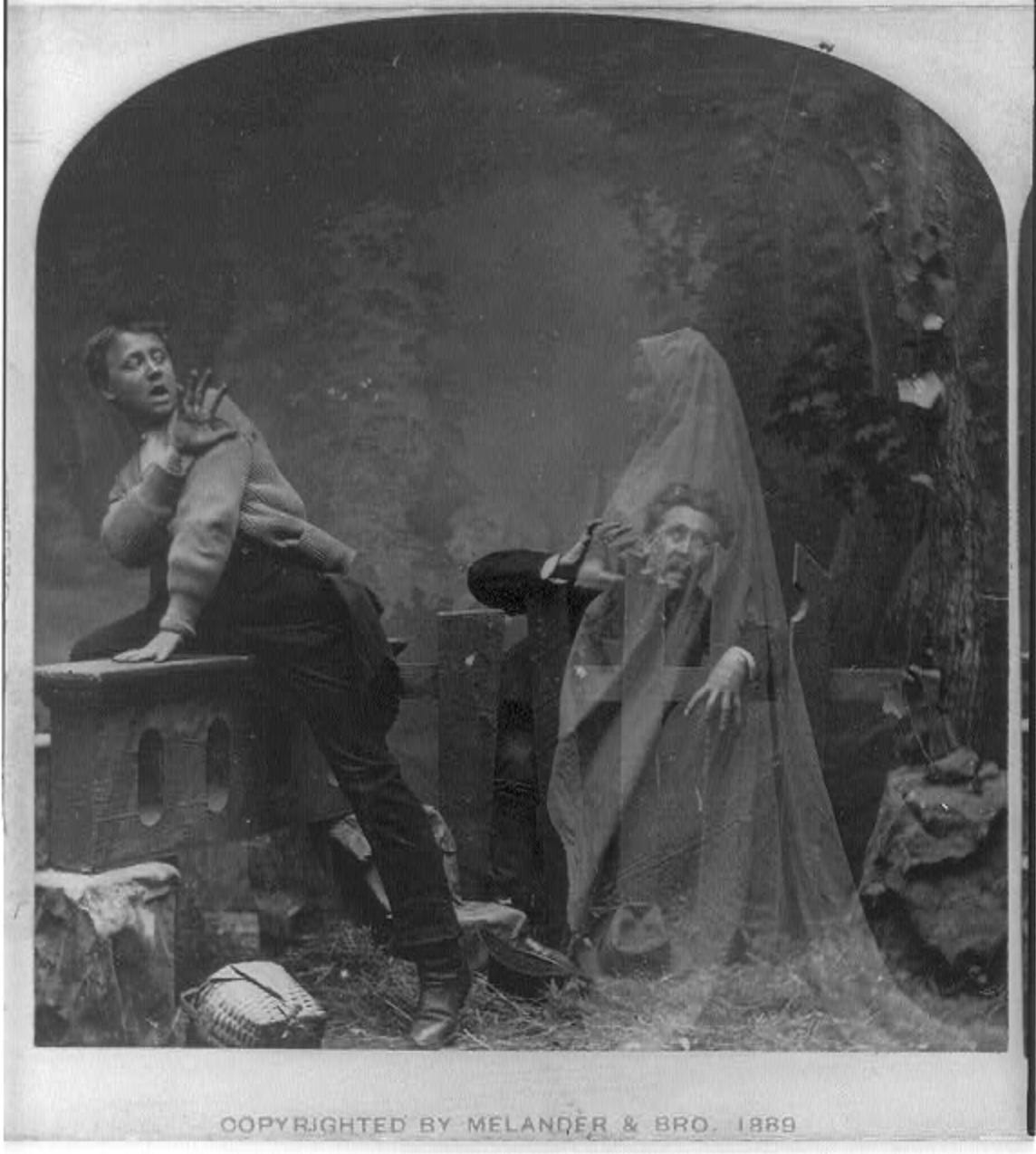

There are louder, harsher, gorier, more violent, and more explicitly Satanic songs out there. There are spookier early Blues recordings, creepier quasi-liturgical works of classical music, and more fucked-up art-music projects. But there’s one spooky song, from a quietly supernatural album, that I’m particularly drawn to this season, week, and night.

So let’s hold a little seance with the album. Pull up a chair.

This album comes from a moment in late-20th century culture where you discern the turning of huge subterranean gears, a dark tectonic realignment. In 1979, just as the first rap recordings were released on vinyl, two music aesthetes met in New York City to collaborate on a new form. They were established artists but hardly stars, craftsmen of post-war technology who shared an art collector’s eye for new movements, a postmodernist's ease with plundering, and a Eurocentric immersion in Black and African music whose unselfconsciousness is, frankly, a bit mystifying now.

The creepy part of this whole thing is that the musical form they were discovering turned out to be the future, the music of the millennium, dimly glimpsed through analog glasses in a 10-track album whose first single, “The Jezebel Spirit,” features demonic exorcism.

Today, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, a collaboration between a 27-year-old David Byrne and a 31-year-old Brian Eno, is haunting, haunted, and, in both the literal and figurative sense, visionary. Famously, it uses "found" recordings as the vocal lines for the kind of funk, disco, and polyrhythmic African groves that would make the Talking Heads' Remain in Light a surging Afro-psychedelic masterpiece a year later.

Byrne and Eno took the album’s title from a folkloric novel by a Nigerian author, Amos Tutuola, that neither one had actually read. But four decades later, the theft feels redeemed since that’s exactly what the album sounds like: a shadowy, static-clouded FM radio wilderness filled with keening, arguing, praying, decompensating ghosts of the 20th century.

Some of which still seem to be running shit today.

Bush of Ghosts is tricky album, definitely a “rich text.” A critic should blanch at its post-colonial appropriations, decry its plundering of Indigenous sacred utterances for "exotic" textures, and engage with the heady questions of context, ownership, musique concrète in this seminal work of proto-sampling.

But I’m sorry, it just sounds too ill to me.

Since I first heard it as a kid, I always have a hard time not perceiving it as a kind of monolith. And as an audio collage it’s antediluvian, an audible product of the late-'70s/early-'80s Manhattan Project that blew up culture as it existed, releasing Public Enemy, Wu Tang, Biggie, Nas, NWA, Dre, Nine Inch Nails, Massive Attack, ambient, EDM, trap, drill, and so many other indispensable vices into the world.

In a way, Bush of Ghosts is like the Saturn V rocket that first brought humans to the moon, a wonder of byzantine engineering across every technical sphere that relied on infernal calculations done with pencils and slide rules. Another epoch-straddling product of geeked-out hyperfocus, the album was assembled from live recordings and physical tape loops: hand-cut, taped together, built on happy accidents and (a guess only) cocaine, amphetamines, or Satanic intervention.

Without anything like digital samplers, Byrne and Eno had to record one tape machine playing the found vocal track and another playing a mixed version of their own instrumental. “And, if the Gods willed, there would be a serendipity,” Byrne wrote in the liner notes of a 2005 reissue. “The vocal and the track would at least seem to feel like they belonged together.”

The fact that they worked at all, never mind sublimely, does make you suspect some spectral presence moving the ouija mixing board. The theory-curious Byrne reaches for psychoacoustics, writing that "the mind found congruences and links where none really existed. Intention had nothing to do with effect... when successful, this effect also 'tricked' the emotions.” It triggered “uplift, ecstasy, dread or sexy playfulness."

But it’s dread and other limbic emotions that animates the album’s single and signature track, the spooky titled “The Jezebel Spirit.” For this song, Byrne and Eno took the vocal line from an apparent field recording of an exorcism, performed on an unheard presumably redacted woman. And today, “The Jezebel Spirit” serves as a test of how willing you are to be tricked.

As a track of recorded music, “The Jezebel Spirit” straddles genres, eras, mediums. The slight tempo fluctuations say it was played live, not quantized, and certain percussion elements — like the struck lower strings of piano's sounding board (00:16) — leave an indelible impression later traced in Trent Reznor's sound design, a chilly undertone of ketamine hangover.

It’s The Blair Witch Project as art-funk. The band ride their noisy, simmering groove for a full minute before the vocalist makes his entrance. The first thing we hear is his disembodied laugh, which feels diabolical in context, and is followed by the query: “Do you hear voices?” (Pro tip: If someone in a clinical setting asks you this, the answer is no.)

After a pause marks the woman’s unheard response, the man continues: “You do. So you are possessed.” He’s either asking for clarification or forcing compliance. “You are a believer, born again and yet you hear voices and you are possessed.” And we’re in.

This audio recording serves the same electrifying role fake digital video plays in found-footage horror films from 20 years later. And it still divides critics. When it came out, the NYT’s long reigning reviewer Jon Pareles reacted against it strongly in Rolling Stone, calling “The Jezebel Spirit” and a similar Ghosts track "a falsified ritual...a pseudo-document [that] teases us by being 'real.'" Reviewing the album's reissue, a Pitchfork critic pointed out that "taping a crazy evangelist has become the art music equivalent of broadcasting crank phone calls."

Both observations are valid and beside the point.

For one thing, this pseudo-document is real. It's a vocal track. And 40 years of media that have been filled with spurious pseudo-documents have only made this particular song realer, both comparatively and in a way similar to the theoretical mode of hyperstition (coined by trailblazing theorist, and later crank, Nick Land) which “transmut[es] fictions into truths.”

For another thing, while the “crazy evangelist” has indeed been a sucker cut for 40 years, that’s not what this track sounds like. While Byrne originally meant to feature a recording of famous evangelical healer Kathryn Kuhlman — who some YouTube viewing suggests would have been pretty awesome, in a Mercedes McCambridge way — the unknown exorcist they replaced her with moves the track into a different register.

Unlike the Southern cliché, this guy is an older man with a mid-Atlantic accent, a vocal presence takes out of arch televangelist-mocking comedy and into some older and creepier missionary context, pulling in tension against the heavy funk vibes and Afrobeat groove. And the fact that her side of the conversation is silent except for bursts of panting breaths, lets the presence of her presumed inhabitant expand in the imagination.

The action is offscreen, but intense, violent. After diagnosing her demon as “a spirit of grief” and “of destruction,” the man rises to the moment, bellowing: “Jezebel!... I bind you with chains of iron!” After which, the recording reveals the scarier contemporary resonance of this song, the speaker’s understanding of this particular bugaboo.

“She was intended by God to be a virtuous woman,” the man bellows — to the demon, to the woman. “You have no right to be there. Her husband is the head of the house. Out Jezebel!” Thus he commands a spirit whose presence is very much alive in the coalition that helped make Madison Square Garden such a grim spectacle here last weekend. A presence who was almost the headliner’s costar, his silent partner.

In fact, the more I learn about the role Jezebel plays in the evangelical imagination, the more this song freaks me out right now. She first shows up in 1 Kings 16, manipulating her husband King Ahab into getting Israel to abandon God and worship the pagan Baal, then lies to get an innocent man killed so she and Ahab can seize his vineyard, then orders the slaughter of the Lord's prophets, and ultimately gets herself thrown out of a window, trampled to death by a horse, and eaten by wild dogs.

Which sure sounds ’70s-horror-film enough for me. But evangelicals see the Jezebel "spirit" in any woman who promotes destructive heresies and leads others into moral compromise. Women energized by a demonic spirit rather than the Holy One. Women who are, you know, more or less the devil, the antichrist, like a certain female veep.

I don’t know how Byrne and Eno managed to use audio fragments from their era as divination bones to roll, tea leaves to read, conjuror tools that showed them the dark, swirling, staticky digital tsunami we live in now. But that’s sure how it sounds right now.

Maybe it shouldn’t surprise us that one of these bones lands on the map in Lebanon. The third track, “Regiment,” which, while kicking ass, is a sampling original sin, taking a stunning a cappella vocal performance of a young Lebanese woman named Dunya Younes from an Islamic music anthology that Eno found in a London record shop, layering it over a deep groove by his own musicians, and releasing it without clearing the sample, without even knowing who the woman really was, though recent reporting corrects this. As for what Younes, her family, and nation are enduring right now, from our current government, the mind skips, seizes, pushes FF.

So Bush of Ghosts still reflects plenty of real and imagined darkness. But despite its dark moody ambience I actually hear hope in it today, maybe even the promise of deliverance.

Two thirds of the way through “The Jezebel Spirit,” after setting up the opposing forces in the found vocal, the musicians sustain tension for a while, the voodoo groove chirping and clattering along until the recorded vocal returns for the final conflict.

We hear the man’s commands, the woman’s gasping exhalations, as he orders her to breathe out, expel the spirit: “Out! Out! In Jesus’s name!”

Whether a charlatan or true believer, this crazy MF-er doesn’t give up. He keeps trying to drag this demon out of her. “Out! Spirit of destruction! Out! In Jesus’s name!” And when I hear that part these days, I’m not listening to an exorcism, I’m participating in one, helplessly projecting into the space of this unheard woman.

“Out! Out!” We hear him expel this demonic spirit from her, from me, from us, from this nation. “In Jesus’s name, Out!”

And at this, the music explodes with color: a twinkling agogo-bell melodic pattern, blinking, glimmering electronics, lighter noisemakers all lifting the groove into a lighter, carnival tonality that feels, as the voices silence, like relief.

The groove continues into a fade-out, the camera pulling out for a wide shot that takes in the larger spectacle, the human drama, and releases the spirits, demons, and psychic ills into the wind.

Call it wishful listening, but that’s how I’m hearing this creepy song this Halloween. There’ll be time enough to find out where the evil spirits went next week.