Being There and Nothingness

Amused, bemused, and confused by the presence of recently departed art icon Frank Stella

Sometime in the past 60 years, our cultural gatekeepers discerned a species of genius distinguishable from moron largely by its dogged, sustained production. Craft, style, wit, insight: such criteria can either drop away or require drastic recalibration in the face of the more spiritual triumph represented by someone bashing away at the same opaque project until everyone says uncle and hands them a MacArthur Award.

I don't have the space or expertise to do a whole genealogy on this, but I figure the shift began with either Andy Warhol's first printmaking lessons or the publication of Barthes' "Death of the Author" essay, and was more or less a fait accompli by the time the Ramones released their debut album in 1976.

Such are the thoughts that come to mind revisiting the career of the minimalist artist Frank Stella, who died a week ago at 87.

OK. I’m obviously off to a bad start here. I happen to be agnostic about Stella's actual work and have only the most superficial engagement with what I’ve seen in person. I get that his canvases advanced a provocative simplicity — repetitive designs of line and color, single-color panels, broad stripes — and made daring use of household materials: commercial enamel, house-painter brush, straight edge.

But since my only response to this has been either to chuckle at their audacity or admire their clean, sharp execution the same way I'd admire a vintage Texaco logo, I’m talking solely about the human presence that emerged in this week’s retrospectives and interviews. And I happen to find this presence — and again, this is just me talking — more provocative than anything Frank Stella the artist created.

The interviews in particular are weirdly riveting. And whether this is due to larger trends in cultural discourse or my own mental illness, they gave me the sense that this guy is messing with me from the beyond.

From the sound of it, this would be pretty on brand. Stella has to be one the more confounding visual artists of his era, which stretched from early '60s abstract expressionism through Pop Art and into whatever you call the pre-to-post-millennial era of large-scale, dystopic, theory-wrapped sculptures about art's value and meaning. Whether he radically changed up his steez to chase trends or because, as the Times says, he was "a master of reinvention," I'll leave it to more informed commentators to say. His early, career-making works are what form the crux of my dilemma.

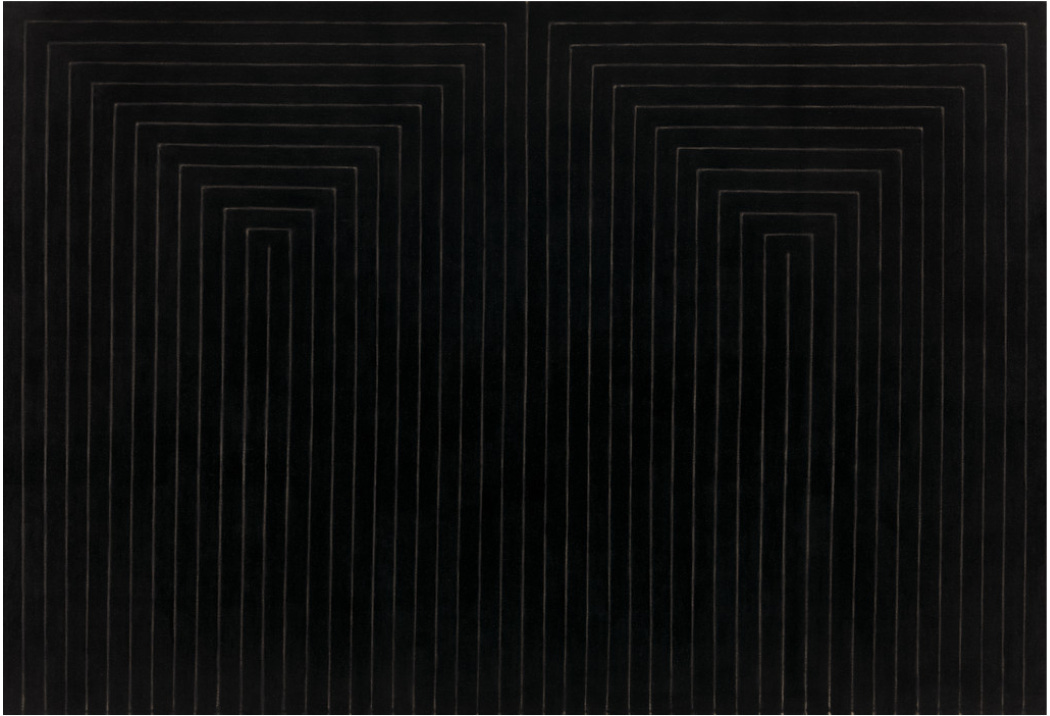

Unlike Pollock's massive heavy-bag workouts or Kline's fluid, masterfully painted monochromes, Stella's breakthrough 1959 works — 24 nearly identical canvases of black, evenly-spaced stripes, executed in his 20s — read like both a rejection of every painterly impulse shown by predecessors like Pollock and De Kooning, and as the Ur-text of my-kid-could-do-that modern art.

Their idea of “deductive structure,” given him by his college buddy, the art critic Michael Fried, posited a visual content derived from the dimensions of the canvas, dictating its division into equal segments. And that’s about as far as I can go iin discussing them.

I’m probably skilled enough with critical formulations, selective quotation, and middlebrow dudgeon to borrow the white suit and write a brief Painted Word broadside against all the eggheads and longhairs who celebrate his legacy. But in these matters I tend to defer to either critical commentary or whatever the artist shares about their ideas, process, ambitions.

The commentary, frankly, scares me.

There's art and there's writing and there's writing about art, and this last rarefied space has hosted some of the most intimidating prose I've ever read, its stars ranging from post-war nuclear physicists like Clement Greenberg to poet aesthetes like the late Peter Schjeldahl. You can quibble with them, but you need either some seriously cold-blooded hustle or a real chip on your shoulder to dismiss their passion, intelligence, and standing offer to open the works up for a curious viewer.

Which leaves the aforementioned interviews. And when the heady realm of abstract-expressionist discourse collides with what Frank Stella actually says, it's enough to freeze your brain.

About 20 minutes into the interviews reposted by NPR, I realized I was spellbound by this man's statements about his life, art, and career. I got the eerie sense that he was playing a much subtler — and therefore more crazy-making — version of the same game Warhol played, only instead of the fey, evasive, instantly quotable banalities whereby Warhol disavowed any meaning or intent to his work, Stella's seemingly thoughtful, earnest-sounding responses only get maddening if you scan them for actual meaning.

In an interview from 2000, Stella tells Gross about his Massachusetts childhood as the son of a gynecologist who'd put himself through medical school by painting houses, often repainting the house they lived in with young Frank's help. Gross asks Stella if this experience was formative.

"Yes, I was in paint all my life," he says. "I liked it. I always liked paint." Since his mother was an artist who did oils and his father painted houses, Stella concludes, "I had paint pretty well covered." Well, good for him.

When Gross asks Stella how he segued from painting walls to painting canvases, he says that he "painted my way through school." By this he does not mean that he financially supported himself as a painter, but that he took art classes at the private boarding academy he attended in leafy Andover, Massachusetts, before heading off to study art at Princeton.

And at this point in the narrative, Stella's soundbites start sketching some weird Chauncy Gardiner line between genius and simpleton, and his career sounds more and more like that of a well-heeled Mr. Magoo who walked straight out of Andover's Phillips Academy into the smallest and most explosive American art scene of the century.

It’s at Andover that Stella first gets the idea of using geometric forms as his subject matter. This happened when an art history course exposed him to the square-based paintings of Mondrian. "It was a tremendous relief to think of the square as subject matter," he tells Gross. "It was easier to paint a square. And I liked doing it besides."

See, the man likes paint and squares.

In his prep-school education, Stella was as teed up for future art success as any young Medici protegé and, at Princeton, his best bud was future career-making ’60s art critic Michael Fried. But despite his privileged training, Stella never condescended to learn draftsmanship or figurative technique.

He relays to Gross how his teacher excused him from such drudgery after he crushed a still life assignment. Shortly after they were given this assignment, Stella and his classmates were shown Seurat and neo-impressionists in their art-history course.

"I said to myself, 'Oh, that's kind of obvious,'" he recalls. "And I ran downstairs to do my painting." He turned in a splotch-assembled rendition of the assigned table, cylinder, and ivy, and showed it to his teacher. "He said, 'All right, all right,' and he let me go. From there on I just did whatever I wanted."

When Terry Gross expresses surprise that the teacher would just roll over like that, Stella says that at 15 he "was a wise guy," then grabs a sports metaphor: "You're the tennis coach and you hit the ball 90 miles an hour and no matter what you do the kid hits it back," he says. "Are you gonna say, 'That's not exactly the right way to do it?'...Either you can hit the ball or you can't."

Again, I'm no art critic, but I know a bad analogy when I read one. Especially when it’s deployed to support the claim that, when young Frank refused to do an assignment, his teacher concluded not that his bratty insubordinate student was too big a pain in the ass to deal with but that he must be a prodigy. A prodigy who preferred splotches and squares.

Fine. The work should speak for itself. But in statements like this, the youthful genius as recalled by the mature artist reminded me of no one more than the youthful genius as recalled by the mature cryptocurrency conman Sam Bankman Fried.

In his book Going Infinite, Michael Lewis relays SBF's experience at math camp, writing that, "by math camp standards, he was only mediocre at puzzles and games. But he also suspected that the sorts of games they played at math camp were too regular for his mind." Which is one of this book’s early indications that its author's head has been spun like a top by his wealthy, famous subject.

Lewis goes on, quoting Bankman Fried: "'The place I am strongest is the place where you have to do things other people would find shocking,' he said. He still had no idea where in the world he might find such a place or if it existed."

May we suggest New York City during a lull in the abstract-expressionist movement?

In 2000, Gross asks Stella if he committed those early black canvases from a lack of interest in color. "Well, I was really learning how to paint," he says. "So I didn't have any particular stake in color one way or the other." He explains that he arrived at the black paintings by taking one of his failed canvases and painting over it. With black paint.

When Gross asks him how he decided to explore working with brash colors, he shares the thought process of a mercenary third grader. "My father said to me, 'You know, people, you need color to sell paintings.' ...And as soon as he said that, the idea popped into my head that I could make striped paintings pretty much the same way I was making them...which would be to use [the paint] as it came out of the can. I thought of red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet."

At some point in these interviews — maybe when Stella said that he found it hard to restrict himself to "artist colors," and prefers commercial paint, possibly "from working as a house painter” — I left my body and half-seriously wondered whether this guy was just saying this stuff to make me mad.

Here's where I should probably also admit that Stella's Boston accent — the same one I've struggled to shed for 35 years — goes some way toward tipping such gnomic utterances into the savant column. I realize that not even the most cerebral artist needs to sound cerebral, and I’ve peeped some of Stella’s own perfectly literate explications of his pictorial efforts. But you still bring certain expectations to bold-faced names from New York City in the Pop Art era.

If Andy Warhol never produced a single silkscreen print, he'd still deserve legend status for his collected epigrams. ("When you do something exactly wrong, you always turn up something.” "An artist is somebody who produces things that people don't need to have." "My idea of a good picture is one that's in focus and of a famous person.") Stella's most enduring quote, from a 1966 interview, is the tautology "What you see is what you see." If someone offered that line to Yogi Berra, he’d think for half and second, and say, “Nah.”

In the Netflix version of The Talented Mr. Ripley, the object of the titular psychopath's obsession, Dickie Greenleaf, is miles less charming than the gorgeous rake Jude Law portrayed in Anthony Minghella's sumptuous 1999 film, partially due to the casting of Johnny Flynn as a big, drawling, generically handsome wasp, but most strikingly due to the "paintings" that his would-be artist shows to Tom.

Bad art as moral x-ray is something Highsmith also explores in other works, like Strangers On a Train, but Netflix’s Ripley goes almost too big and broad in the pictures that they produce for the profoundly talentless Mr. Greenleaf. In fact, these things are more damning of his character than if he'd tripped an old lady or kicked a dog. Even worse, they're revealed right before Dickie takes Tom to a nearby church to see its Caravaggio, whose poetic chiaroscuro brutally rebukes the memory of this punk dilettante’s swipes at Cezanne, Picasso, Matisse, which are so fumbling, hackneyed, and literal-minded you want to strangle the guy yourself.

"That's my abstract period," Dickie says Andrew Scott’s scalded-looking Ripley stands gaping at a canvas whose line drawing portrait has the eyes placed atop each other in a comic-strip version of early Cubism. "I know I'm not a great painter,” Dickie allows. “Yet.”

I thought of this scene when I listened to Stella recall a moment, some 30 years after he skipped technical instruction at Andover, when he’s at Rome’s Capitoline Museum and first sees Caravaggio's “Young St. John the Baptist.” Did being in the presence of this consummate technician, whose sense of form and light touch the sacred, make Stella feel in any way inadequate? Hardly.

“I should have said, 'Oh my God, I can't do this,' and I should have been very worried about this,” he admits to Terry Gross. “ But the effect was the opposite, it was a kind of incredible euphoria, of saying, you know, 'That's it, that's what painting is about. I realized that Caravaggio's success, and what made his paintings beautiful and its sense of being very real, very physically present, had nothing to do with the technique.”

Let’s all give up for this audacious take on Caravaggio. And let’s celebrate the bone-deep self-confidence it implies. Stella’s contention is that Caravaggio’s “success had to do with the fact that he worked very hard at painting,” he tells Gross. “And that he had wanted to make a painting. That's when I realized that the goal is what counts. It's what you intend to do…The technique you use to make the pictoriality manifest doesn't really matter. You get the job done.”

That much is irrefutable. And at such points, I wondered if I hadn’t fixated on this guy out of some lopsided Jungian shadow thing, where he was just a handy receptacle for various doubts and anxieties I have in producing things that people don’t need to have.

Frank Stella did indeed get the job done — over and over and over again, for more than 50 years. And isn’t that what people like us are all doing here, week after week? Writing our essays, posting our photos, accepting the klinkers, enjoying those that land, always focused on the next one, on creating and solving its problems?

“I never felt like an artist,” Stella tells Gross. “The only thing I have is the will to make paintings.” And after this, he drops the funniest bit of commentary in all the interviews.

He says it after Terry Gross asks him which incisive, apt, or unsympathetic response he ever got from critics really got to him in the early years.

“Well, I had a hard time with criticism," he begins, at which point I steeled myself for some version of the dismissals that cultural icons from Samuel Beckett to Stravinsky, Frank Zappa, and David Lee Roth have given criticism. I was not prepared, though should have been, for Stella’s complete recusal from the entire subject.

“The writing about it was really a little bit beyond me,” says this person whose constant production of two- and three-dimensional objects filled pages, books, academic papers, and posts such as this one. “I was a relatively unsophisticated person in that way,” he continues. “I really wasn't interested in philosophy or in the notion that you could appeal to smart people by saying smart things about painting.”

And so, with one sweep of a Benjamin Moore paintbrush, does a perfectly savvy traveler in the professionalized art world of the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s — an artist who presumably played its games well enough to be employed and relevant throughout the upheavals and increased dominance by market forces — reclaim the moral authority of naif.

“I just wanted to make paintings that I liked,” he says. “I didn't care if smart people liked them.”

At which I can only say “uncle.”

May Frank Stella be happy. May he be well. May he rest in peaceful ease. And may all creative people find his self-acceptance, as well as the time and the resources to sit down and get the job done.

Nice play on words via the title of one of my favorite books: Being and Nothingness by Jean-Paul Sartre.

Who'da thunk, a modern-age essay on art as Phenomenological Ontology with Ramones temporal points as parameters - sheer genius (good read too).